A Backpacker's Life by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photography: Devil's Tower

I took this photo in 2012 at Devils Tower National Monument in Northeast Wyoming, USA.

You can purchase prints of my photos in my Etsy store. Orders are greatly appreciated!

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO

The winding road to Devil's Tower was hilly, green, and smelled of pine. It appeared when I was still six miles away, as a lonesome faint blue column soaring out of the ground. I've seen lots of photos, but it’s bigger than the image I carried in my head. You know how when you see a celebrity they always seem shorter in person? Well, imagine meeting Kevin Spacey and he's 1,208 feet tall!

Just accept that that analogy is perfect and continue.

I wondered what pre-scientific people thought when they first saw this strange monolith emerge through the atmosphere from far away. Such an odd thing would surely generate legends. I didn't have to wonder long though; a roadside plaque told me one such legend…

Native American's told of seven little girls being chased onto a low rock by attacking bears. The seven girl's prayers for help were heeded. The rock carried them upward to safety as the claws of the leaping bears left furrowed columns in the sides of the ascending tower. Ultimately, the rock grew so high that the girls reached the sky where they were transformed into the constellation known as the Pleiades.

Definitely an interesting story, but I think science is often better than fiction. In reality, ancient seas ebbed across this part of North America, including all of Wyoming, and split the continent into two. Silt, sand, and other rock fragments got deposited on the sea floor and formed soft sedimentary rock. 50 million years ago, molten rock pushed up through that sedimentary rock a mile and a half below the earth's surface and became a harder igneous rock that cooled and fractured into columns as it crystallized.

As eons passed, erosion more easily stripped away the softer rock around Devil’s Tower, leaving the 1,208-foot column. Knowing how long such a process takes, makes me more passionate about protecting it, and more grateful for our National Parks.

Now, the Pleiades on the other hand, those formed out of seven little girls. They got that part exactly right. Any scientist worth his salt will tell you the exact same thing.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

30 Tips for Hitchhiking to Resupply

|

| (Photo: Liv hitching in Maine) |

On a long enough hike, hitching into town to resupply is almost a necessity and often a major concern for aspiring thru-hikers. The first time I stretched out my arm and put out my thumb, I felt equally nervous and excited.

A couple hundred hitches later, the nervousness dwindled to nothing, but the excitement continues. It's not simply free transportation. Something about it evokes a feeling of uncomplicated freedom. Akin to minimizing possessions to only what you can carry.

My friends and I have gotten many hitches from people who said we were the first hitchhikers they have ever picked up, so it seems we’re doing something right. Not everything here is essential for getting a ride, but they are all of the things I consider. The tips are geared toward the short hitches between trails and towns for resupplying, but most of them apply no matter where you’re hitching.

A couple hundred hitches later, the nervousness dwindled to nothing, but the excitement continues. It's not simply free transportation. Something about it evokes a feeling of uncomplicated freedom. Akin to minimizing possessions to only what you can carry.

My friends and I have gotten many hitches from people who said we were the first hitchhikers they have ever picked up, so it seems we’re doing something right. Not everything here is essential for getting a ride, but they are all of the things I consider. The tips are geared toward the short hitches between trails and towns for resupplying, but most of them apply no matter where you’re hitching.

Look for a spot where someone can easily pull over without issues or in places where it would be illegal to stop. Wide shoulders and turnouts are prime real estate for hitching. This will be the most obvious thing you'll read on this list, but also be sure you're on the side of the road where the traffic is moving in the direction you want to be going.

2. Give time for drivers to see you and brake safely

5. The Law

8. Hitch in pairs when possible

16. Wear something bright

26. When all else fails, just look as pathetic as possible

Tips for after someone has taken the bait

27. Tell them the shortest distance you’re willing to go on the hitch

Tips for when you’re in the car

29. Have a good conversation

There will be exceptions to all these tips. They are simply things that may help increase your chances of getting to where you need to go.

Hitching isn’t without risk, of course, but it’s not as dangerous as most people believe. As with everything, firsthand experience reduces your fear by making you more aware of reality.

People often say, “I wouldn’t hitch in this day and age.” Those people need to stop watching TV. The news is to reality what reality shows are to reality. Get out and see the world as it really is. Believe it or not there are fewer acts of violence today than ever before. The number of people willing to injure or murder a stranger with his thumb out on the side of the road has not gone up, in fact, it has gone down.

Actually, come to think of it, people have picked us up because they were afraid if they didn't a crazy person might. So maybe a little bit of fear in the population is good for hitchhikers.

Take precautions, but don't let a fear of hitchhiking keep you from attempting a thru-hike Besides, you may find that many of your best stories of the long hike are your hitchhiking stories.

Stand in a spot where a driver will have a few seconds to see that you’re hitching and have plenty of time to slow down. And of course, enough time to take pity on you. Few people will want to slam on their breaks or turn around to pick you up. It happens occasionally, but don’t make it a requirement.

Standing by a road sign or anything else that a driver might already be looking at, may give them an extra second to notice you.3. Put your thumb out and pointed up, if in the United States

This might seem obvious, but I mention it because the tradition of putting out a thumb is what we do in America and Europe, but it's not the standard everywhere. If you’re in another country, you’ll want to learn their gesture. For example, in Israel, hitchhikers hold their fist out with their index finger pointing towards the road.4. Hitch where traffic is slow or stopped

Such as near traffic lights or within eyesight of where people are pulling out of gas stations or parking lots. While waiting for a light or pumping gas they are more likely to notice you. Perhaps the best spot is right before a highway on-ramp.

|

| (Photo: Me hitching by the Inn at Long Trail) |

The law can seem a little complicated, so I’ll try to simplify it:

Although rarely enforced, hitching is illegal in Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and New Jersey.

It is illegal to hitch on Interstates except in Texas, Oregon, North Dakota, and Missouri. This doesn’t mean you can’t hitch on the road that leads to an Interstate on-ramp though.

Although, most states prohibit standing on the road itself, it is usually okay to hitch from the shoulder. If you're unsure, stand just off to the side of the shoulder. It's safer anyway.

California, Alaska, Hawaii, Washington, Kansas, Wisconsin, Florida, Maine, New York, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts have more complicated laws that you may want to read up on. I’m not going to go into them here, but I will just say if you’re outside city limits in these states it’s usually okay to hitch. Although, failure to read up on these laws could result in a citation. It's rare, but it happens. Just remember that I warned you.

The police may ask for your ID even if you’re not doing anything unlawful. Just let them, even if you don’t technically have to identify yourself when not breaking any laws. They are usually just trying to keep people safe.

Sometimes it’s illegal to hitch on other federally-owned roads other than Interstates, like National Park roads, National Scenic Byways, and National Recreation Areas, but I’ve never had any trouble. A park ranger in Yosemite even once suggested I hitch to a certain trailhead since their buses did not go out that far.6. Minimize Turns and Simplify Your Route

The less complicated your route, the more likely a person driving by will be heading to your destination. If you’re a few blocks from the first turn, go ahead and walk that distance to eliminate it from the route. The more turns and on-ramps that you eliminate from your route, the better. By all means, stick your thumb out as you walk, but toward that better position.7. Don’t get dropped off in a bad hitching spot

If you’re going to need multiple hitches to get to where you’re going, don’t get dropped off in the middle of nowhere even if it’s closer to your destination. If they will have to drop you off between towns where there is little to no traffic, thank them for stopping, but wait for the next hitch.

Also, it’s harder to get a hitch from downtown. Traffic will be going in every direction and people aren’t necessarily driving out of town. If someone has to drop you off in a town you’re not staying in, ask to be dropped off at the edge of town instead.

|

| (Photo: Red in the back of a pickup while hitching in Gorham, NH) |

This may also mean separating a larger group into pairs. People aren’t just giving you a ride, but your packs as well, which take up a lot of space. Hitchhiking is a numbers game, and if you’re in a big group, you’re going to have fewer vehicles pass that could possibly carry you all.

Consider having all but two standing off to the side where they aren't seen from the road. If someone stops that has the room, ask if they can take you all. Otherwise, leave the rest behind and meet back up in town.

Also, when possible, have one female to each pair. Couples and women are a lot less threatening to motorists. When I was hitching with Sixgun and Liv, there were many times when we'd put our thumbs out and a car would stop almost immediately.9. Be Happy

If you’re not happy, fake it. People don't want to pick up a stranger who looks angry or dangerous. If you’re with someone else, have a happy conversation while you’re holding out your thumb. Laugh, even if what is said isn’t that funny. Tell jokes if you have to force it. You’ll seem friendlier.

Although, don’t exaggerate your happiness or laughter. I was with another hiker on the AT trying to get a hitch and his over-sized smile and exaggerated attempts at physical humor were just creepy. Nobody stopped.10. Don’t have a knife sheathed on your belt

If you want to have one in your pocket for safety, that’s fine, although 99.9999% of people are stopping to help a fellow human, not harm them. Anyway, they are usually more afraid of you than you are of them, so put the knife out of sight.11. Make Eye Contact

Eye contact can really increase your chances of getting a ride. If someone makes that simple connection with you, I think it adds a little bit of guilt or pity to their quick decision making. In this scenario, guilt and pity are your friends.

Of course don’t stare at them in a creepy way, but give them a friendly smile. If walking, turn around and walk backwards with your thumb out when a car is coming, so you can still make that eye contact.12. Take off your sunglasses

Let them see your non-threatening face. If your face is just naturally threatening, I don’t know what to tell you.13. Don't Smoke

A lot of people don't want cigarette smoke in their cars. Smoking can definitely reduce the percentage of cars that will pick you up. And they will already have your hiker odor to deal with. If you need to smoke, ask after you're on the move if they mind.14. People Sometimes Come Back

If the speed of the car makes it obvious they are not going to stop, smile and wave anyway like you’re thanking them for the consideration. Show them this common courtesy and sometimes they will turn around and come back for you. Guilt and pity sometimes takes a second to brew.15. Look as clean as possible.

If someone thinks they’re going to have to get their car’s interior detailed after driving you three miles, they’re probably not going to stop. And if they do pick you up, actually being clean may make them tolerate taking you further. In other words, do whatever you can to freshen up.

|

| (Photo: Red and Cocoa Toe hitching from Asheville, NC back to the Appalachian Trail.) |

When you’re buying a shirt or bandana for your hike, consider the brightest ones possible. They could help you get noticed when hitching.17. Talk to people near trailheads

If you know you’re going to try to hitch at the next trailhead, parking area, or road, start talking to day-hikers that you meet on the trail. You don’t need to ask them for a ride, but later, when they see you standing by the road with your thumb out, they will often pick you up. Even just asking them for the time or commenting on what a beautiful day it is can be enough.18. Talk to people in town

The same thing applies in town. While you’re in grocery stores, convenience stores, or restaurants, talk to people. Some business owners frown on you soliciting a ride from their customers, but you don’t necessarily have to. If you’re being friendly and talking to people, they’ll often pick you up when they see you hitching later. Just make sure they see you, hitch in eyesight of the people pulling out of the parking lot. If you see someone that you had a conversation with, wave to them so they know it's you.19. Don’t bother hitching on the side of the road at night

Instead, go to bars, restaurants, or well-lit gas stations and meet people. Again, business owners don’t want you walking up to customers to ask for a ride and most people don’t like it either. Start conversations first and mention where you’re headed. They'll see your packs, they know you're travelling. Often they will offer the ride and think it was their idea the whole time.

Besides, standing on the side of the road in the dark could be dangerous.20. Ask people about public transit

Sometimes I feel weird asking people for a ride, especially on a business's property, so I resort to a more passive indirect way of doing it. Sometimes I’ll ask the employees of the business or the locals if they know of any public transit services in the area and tell them where I’m headed. Often they’ll just offer you a ride. Remember, it’s always good to find ways to make the ride seem like their idea.21. Stand and Pace to get noticed

But don't walk away from a prime hitching spot. Only walk while hitching if you're moving to a better place. I've walked toward town while hitching while other hikers stayed back to hitch and they ended up passing me. Something you realize after walking in the woods for hundreds of miles is that cars are incredibly efficient at moving people around.22. Keep your backpack on or in plain sight

If people can see your pack or trekking poles, and you’re near a trail, they will often know your just a hiker needing to resupply in town. This means you probably aren’t going far and probably aren't there to murder anyone.23. Make Signs

I'm still not sure if signs really help, but it's something to consider. One time on the Long Trail, Red and I made one. I asked the guy, “So did the sign help out at all?”

“Actually,” he said. “I didn’t even notice the sign. The first thing I noticed was the kilt.” Red hikes in a kilt. When he bought it, I was certain we’d never get another ride again, but I was proven wrong many times.

If you’re already carrying a colorful bandana, use that instead of cardboard. It doesn’t add weight to your pack, it will stand out, and if you use cardboard people may just assume you’re "willing to work for food" instead of looking for a ride.

When making a sign, make it as simple as possible. This ensures it's easier for a driver to read and it will be reusable. It can be as simple as the letter of the direction you’re going, for example on a north/south running trail, you’ll probably only need an E on one side and a W on the other. You could also write something even more generic and reusable like, “Hiker to Town,” on one side of a bandana and “Hiker to Trailhead” on the other.

If you get too specific and write your actual destination on a sign, not only is it not reusable, but if the destination is further away or in a direction the driver isn't going, they may not bother to stop at all. And you really want them to stop. If they have already made the effort to stop, they are more likely to take you where you’re going or at least get you part of the way there.24. Consider the time of day when you’ll get to the road

Obviously, you don’t want to get to the road after dark, but get there at least an hour before dark in case you don’t get a ride right away. Think about how many miles you have to the road and how much time you’ll need in town. If you want to get back to the trail before dark, leave enough time to shop and get two hitches. Usually two or three hours is plenty unless you're in the middle of nowhere.

Also, remember that a lot more people go on day-hikes on weekends, so you are more likely to see cars parked at trailheads and so more likely to get a ride.25. Sometimes going in the wrong direction will get you to your destination quicker

If you’re in a bad spot and you can’t get a ride in the right direction. Try to also get a ride to a better hitching spot in the other direction.

|

| (Photo: Sixgun and Liv hitching in the rain) |

Being rained on helps. So does taking off your coat and looking cold. Sometimes desperate times call for desperate measures.

Tips for after someone has taken the bait

27. Tell them the shortest distance you’re willing to go on the hitch

For example, when someone asks where you’re headed, say something like, “Well ultimately, I need to get to _______, but if you can take me to _______ that would be great!” That way they won’t feel like they’re stuck with a smelly hiker for a long time, but if they like you, they’ll usually take you further. Actually, I think everybody except two people took me the full distance even if it wasn't on their way, but in their defense both of them were expected to appear in court.28. Be leery of putting your pack in someone’s trunk

They might just pull away with all your gear when you get out. Either on accident or on purpose. Just imagine being dropped off by a trailhead and helplessly watching all your gear roll away. Instead, put your pack on your lap, or if you're in the backseat set it right next to you. If you’re hiking with someone else, have a rule that one person stays in the car until the other has pulled the packs out of the trunk.

Tips for when you’re in the car

29. Have a good conversation

Don’t just sit there quietly the whole time. That’s weird and they will be less likely to take you that extra distance. Ask them where they are from. Be happy. Tell them about your travels. If they enjoy your company, they are more willing to take you the extra mile or pick you up again if they see you hitching back to the trail.

Tell them interesting stories, but try to get them to talk about themselves. Not only are some of these people really interesting, but people like talking about their lives. If they are enjoying the conversation, they will usually drive you further.

I’ve had many people go out of their way to take me where I needed to go. After finishing the John Muir Trail, a driver drove me two hours out of his way to take me back to my car in the Yosemite Valley (four hours round trip). We had a great conversation. Not only that, but I’ve had people drive around to look for me later to take me back to the trailhead.

Never talk about anything even remotely controversial. This should be a given, but if the driver brings up the topic, just smile and nod or try to change the subject. I know some people can’t help but argue, but you have to fight the impulse if you want them to take you further or pick you up again later. Or just agree with them, if doing so doesn't kill something dear inside of you.30. Be courteous

Apologize for the hiker smell and thank them for the ride. These people are doing you a huge favor and all you’re offering is your stench. Make sure they know how grateful you are for their kindness. When people think you like them or appreciate them in anyway, they will like you almost 100% of the time. I’ve had people wait for me to finish shopping and drive me back to the trail. People are just amazing sometimes. Make sure they know that.In Conclusion

There will be exceptions to all these tips. They are simply things that may help increase your chances of getting to where you need to go.

Hitching isn’t without risk, of course, but it’s not as dangerous as most people believe. As with everything, firsthand experience reduces your fear by making you more aware of reality.

People often say, “I wouldn’t hitch in this day and age.” Those people need to stop watching TV. The news is to reality what reality shows are to reality. Get out and see the world as it really is. Believe it or not there are fewer acts of violence today than ever before. The number of people willing to injure or murder a stranger with his thumb out on the side of the road has not gone up, in fact, it has gone down.

Actually, come to think of it, people have picked us up because they were afraid if they didn't a crazy person might. So maybe a little bit of fear in the population is good for hitchhikers.

Take precautions, but don't let a fear of hitchhiking keep you from attempting a thru-hike Besides, you may find that many of your best stories of the long hike are your hitchhiking stories.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photo: Rainbow at Yellowstone Falls

You can purchase prints of my photos in my Etsy store. Sales will be used to fund a replacement for my broken camera before my Pacific Crest Trail hike, so orders are greatly appreciated!

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO

I slept in my car, so I could wake up before sunrise to get a specific picture. On my first Yellowstone visit in 2004, I tried to get a photo of the falls, but it didn't turn out very well. I wanted to try again.

I wasn't the only person who lugged a camera and tripod up to the view of the lower falls in "The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone." A row of photographers were already there quietly watching the sunlight melt down the canyon's yellow rock.

I did have the oldest crappiest equipment though. I felt like a kid from the Mighty Ducks with a worn-out jersey and hockey stick held together with duct tape, just trying to compete against the spoiled rich kids with their expensive new gear.

I still wasn't happy with the pictures I was getting, but I heard that from a certain angle, the sun and the mist from the falls produces a rainbow around 9:30, so I searched for a better place to set my tripod.

In the end it was worth waking up cold and groggy in my car. I'm much happier with the picture this time. There is just something about devoting an entire morning to getting a specific photo that makes me love this one even more. There are hours of great memories packed into this fraction of a second.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Q&A: Should I Buy Hiking Shoes or Boots?

|

| (Photo: My Keen Boots after 900 miles on the AT) |

I laughed as few people could. “So did you bolt out of sleep screaming while lying on sweat-soaked sheets?”

The nightmare was sort of my fault. Earlier, I had been replying to a reader’s question about footwear and I asked for his opinion.

“I just woke up confused, thinking, did I actually buy boots?” he said. “Why would I do something that foolish?”

This great question comes from a reader named Heather. I like this question because when buying your first set of gear, certain items seem like a given. Football players need cleats, basketball players need high-tops, and hikers need sturdy leather hiking boots, right?

My quick answer is that unless you are bushwhacking through rough terrain, slogging through bogs, hiking in deep snow or very cold weather, or there are other safety concerns, go with shoes. Specifically shoes designed for trail use that are:

- Lightweight

- Breathable

- One size bigger than your actual foot size and

- Have a sturdy sole that is slightly wider than your foot and not too elevated

- Have a spacious toe box

Reason #1: Shoes Are Lighter

When you put on a good pair of boots, I admit you do feel strong, like you could bulldoze through any terrain unscathed. On the other hand, a good pair of trail runners makes you feel light and fast, which is what I want. If I were doing a lot of bushwhacking or hiking through miles of cacti, perhaps I’d want a high-top leather boot, but I rarely find myself in that situation as I generally stick to designated trails.

Reason #2: Shoes Dry Quickly

When thick leather boots or Gortex boots get wet, they stay wet for way too long. Long enough to cause foot problems. I've given up on the idea that you can keep your feet dry. Whether it’s precipitation or perspiration, water will get in eventually. When it does, you don’t want your feet staying wet for very long. Soggy feet are much more prone to blisters and chafing. Hiking shoes made with breathable synthetic materials, or mesh, which will dry much more quickly.

Having an extra pair of dry socks is also important. When putting on a dry pair, I hang the wet socks on the outside of my pack with safety pins to dry while I hike. At the end of the day, I keep any damp socks in my sleeping bag, so my body heat will dry them out overnight.

Reason #3: Shoes Don’t Need To Be Broken-in

On a long enough hike, you’ll have to stop for new shoes. In my experience, until new boots are broken in, I'm more susceptible to hot spots and blisters. A good pair of trail runners, on the other hand, are usually comfortable out of the box.

|

| (Photo: My "$780" pair of shoes) |

My first 300-400 miles on the Appalachian Trail, I hiked in a pair of Inov-8 trail runners. I could roll them up like a pill bug with little resistance from the sole. They only cost about $80, but about $700 in medical bills.

The problem was the flimsy sole. As a barefoot runner, I believed the less my shoes unnaturally constrained my foot the better. I still believe there may be some truth to that, but it isn’t natural to carry 30 lbs. on your back and hike on rough terrain for months. I learned the expensive way the importance of sturdy soles.

|

| (Photo: My rugged barefoot runner feet are blister-proof) |

Ankle Support

It may seem like high-top boots offer more ankle support, but I’m skeptical about that. Besides, my nonprofessional opinion is that the sole has a lot more to do with ankle protection than the high-top collar.

For example, ankle sprains are much easier with a narrow sole and they are much more severe if the sole is too thick. A wider base will help prevent your ankle from turning and the higher your foot is elevated the higher your risk of injury.

Try on a pair of shoes and sort of roll your foot side to side. Do the shoes roll easily? Do they feel like you could easily twist your ankle in them? Is there a threshold where when you turn your ankle the shoe wants to suddenly snap to the side? If so, try another pair.

|

| (Photo: My Salomons, My Personal Favorite) |

This is another important quality in a sole. Trail shoes need good traction, especially with those prone to falling like me. My Salomons have a deep tread on the bottom that grip rocks and roots very well, even when they're wet.

Actually, I can't recall falling since I purchased my Salomons. Tell anyone who has hiked with me long enough and they would gasp in disbelief.

To conclude, in my experience, you want a sole that is:

- Sturdy, so can't be easily rolled like a pill bug

- A little wider than your foot

- Not too thick or elevated

- Has good traction

Find a shoe that fits properly then buy one size larger than normal

It's normal for feet to widen after backpacking for a while and they tend to swell after hiking long distances. Due to this, I've learned to buy a full size larger than I need.

Make sure your foot doesn't slide around too much in the shoe. This will lead to hot spots and blisters. A properly fitted insole with a deeper heel cup will help prevent this.

I have slightly wider feet than normal, so much so that the first hole I get in most shoes will be right next to my pinkie toes. Therefore, I prefer a wider toe box. Along with some rubber on the front, the extra room in the toe box will also protect your toes when you kick rocks and roots. And you will, many many times.

Try on multiple pairs and brands, A Plug For Zappos.com

Try on several brands. Many people swear by their pair of Merrells, but the two pair of Merrels I tried destroyed my feet, one pair had me limping in less than 5 miles. They just don’t work for me. I love my Salomons, but they may not fit other feet as well.

Before hiking the Appalachian Trail, I ordered about ten pair of shoes on Zappos.com. I kept my favorite four, and then returned the others. Zappos has free 1-2 day shipping both ways, competitive prices, a large selection of hiking shoes, and a 365-day return policy. This allowed me to have extra pairs of shoes at my sister’s house in case I needed her to send me a new pair. When I finished the trail six months later, I followed their incredibly simple return process and got my money back on the unused pairs.

Possible Benefits of Boots

High-top boots tied close to the ankle may keep out some debris, but I don’t find debris to be too much of a problem. It really depends on the terrain. Actually, Red told me he had more issues with debris getting in his boots than in his trail runners.

Either way, we both find that the low collar of a shoe makes it much easier to scoop out the debris with your finger without taking the shoe off, unlike high-top boots. Also, when your shoes need to be taken off to dump out debris, my Salomons with their zip cord style laces, are easy to take on and off without even sitting down. Cleaning out boots is a longer process.

|

| (Photo: Dirty Girl Gaiters) |

In my mind, the only good reason to buy boots for multi-day backpacking is if you will be hiking in deep snow, waterlogged bog or marsh, doing a lot of bushwhacking, or hiking in atypical or extreme environments. For example, in very rough terrain, high-top boots may protect your ankle from scratches and bumps, especially that bony protrusion on the outside of your ankle.

Durability

It may be true that a quality heavy boot will last longer, but that hasn't been my experience. I got about 900 miles out of both my Salomon trail runners and my last pair of heavy mid-high boots. Even if they didn't last as long, I want to be hiking those miles on happy healthy feet.

Other Considerations

Camp shoes

Good trail runners are so comfortable that I don’t see the need for camp shoes. Which reduces some weight and bulk in your pack. The only exception is if I’m going to be fording rivers or streams, I might carry a pair of lightweight Crocs.

Camp shoes

Good trail runners are so comfortable that I don’t see the need for camp shoes. Which reduces some weight and bulk in your pack. The only exception is if I’m going to be fording rivers or streams, I might carry a pair of lightweight Crocs.

Stream crossing

On a warm sunny day, you may not even need to remove a breathable pair of trail runners to cross a stream. Many of them will dry after only 15-30 minute of hiking. I do recommend removing your socks and insoles before crossing, though. When you put them back on, they will draw some of the moisture out of the shoe and allow everything to dry much faster than if everything is saturated completely.

Socks

Don't be alarmed by the cost of a good pair of socks (usually $15-20 per pair). My favorites are the Darn Tough Vermont brand. Not only did my first pair last from New Hampshire to Tennessee on the A.T. (until accidentally setting them on fire when drying them out by a campfire), but Darn Tough replaced them.

I walked into the Outdoor 76 outfitter in Franklin, North Carolina and saw a sign that said the Darn Tough brand was "Unconditionally Guaranteed". I jokingly said, "Unconditional? What if you were to accidentally set them on fire?"

To my surprise he said, "Yeah, bring 'em in."

I pulled the smelly socks from my pack, he held out an empty plastic bag with his nose turned to the side, and I dropped them in. He quickly tied the bag shut like they were radioactive then let me take a free pair off the shelf. I suspect that other outfitters will tell me to send them back to the manufacturer to get the replacement, but after that I became a Darn Tough Vermont man for life!

Sock Liners

I don't usually use sock liners, but they have been essential a few times when hiking in rain or snow all day. They can cut back on chafing and protect your softer water-logged skin from blisters. I use toe sock liners to add more protection between my toes.

Final Thoughts

I've seen people hiking in boots who had infected blisters and toenails falling off. There's just no need for that. If you are getting a lot of blisters, hot spots, or having other foot issues, don't believe that it just comes with the territory. Do what works for you, but if your footwear isn't working, change as soon as possible.

Similarly while hiking, if you start to feel a hot spot on your foot, stop immediately and try to fix the problem. You may need to clean debris out of your shoes, put on dry socks, stick a piece of duct tape inside your shoe where your foot is rubbing, or put a bandage on a potential blister spot. Failing to do so right away may lead to a bad time on the trail.

Your feet are your only vehicles out there, they will take you to some of the most amazing places in the world and the best experiences of your life. Treat them accordingly.

Thanks for the question Heather! As you know, I love talking about this, so keep the questions coming! If anyone else has a question or comment, you can use the links at the top right of this page to contact me.

Read more about foot care for backpackers in my interview with the president of the American Association of Podiatric Sports Medicine, Paul Langer: http://ryangrayson.blogspot.com.es/2014/03/footcare-for-backpackers-part-1.html

I walked into the Outdoor 76 outfitter in Franklin, North Carolina and saw a sign that said the Darn Tough brand was "Unconditionally Guaranteed". I jokingly said, "Unconditional? What if you were to accidentally set them on fire?"

To my surprise he said, "Yeah, bring 'em in."

I pulled the smelly socks from my pack, he held out an empty plastic bag with his nose turned to the side, and I dropped them in. He quickly tied the bag shut like they were radioactive then let me take a free pair off the shelf. I suspect that other outfitters will tell me to send them back to the manufacturer to get the replacement, but after that I became a Darn Tough Vermont man for life!

Sock Liners

I don't usually use sock liners, but they have been essential a few times when hiking in rain or snow all day. They can cut back on chafing and protect your softer water-logged skin from blisters. I use toe sock liners to add more protection between my toes.

Final Thoughts

I've seen people hiking in boots who had infected blisters and toenails falling off. There's just no need for that. If you are getting a lot of blisters, hot spots, or having other foot issues, don't believe that it just comes with the territory. Do what works for you, but if your footwear isn't working, change as soon as possible.

Similarly while hiking, if you start to feel a hot spot on your foot, stop immediately and try to fix the problem. You may need to clean debris out of your shoes, put on dry socks, stick a piece of duct tape inside your shoe where your foot is rubbing, or put a bandage on a potential blister spot. Failing to do so right away may lead to a bad time on the trail.

Your feet are your only vehicles out there, they will take you to some of the most amazing places in the world and the best experiences of your life. Treat them accordingly.

Thanks for the question Heather! As you know, I love talking about this, so keep the questions coming! If anyone else has a question or comment, you can use the links at the top right of this page to contact me.

Read more about foot care for backpackers in my interview with the president of the American Association of Podiatric Sports Medicine, Paul Langer: http://ryangrayson.blogspot.com.es/2014/03/footcare-for-backpackers-part-1.html

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photo: Grinnell Lake

I took these photos in 2012 in Glacier National Park.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

In the heart of Glacier National Park, beyond the waterfall and over the ridge, is Grinnell Glacier. While slowly migrating and freezing and thawing, it grinds against the rock and generates silt-sized particles called glacial flour. As the glacier melts, this glacial flour gets suspended in the water then flows over the falls and into Grinnell Lake, turning what would have been an ordinary mountain lake into this turquoise gem tucked away in the mountains.

Homesickness

“Hey Red, do you remember that day on the Long Trail when we hiked into Brandon, Vermont?” Red had called to talk about backpacking again, a kind of weekly therapy for being back in the real world. “I was thinking about that today. We woke up freezing and then it rained on us all day.”

“It rained almost every day on that trip,” he said.

“True, that rain was relentless. I don't think we had two days in a row without rain on that trip," I said. "We hiked seventeen miles of muddy trail to the road then decided to hitch to the McDonald's in Brandon, so we could be warm and dry for a change.”

“Except, nobody picked us up,” he said.

“Yeah, so we ended up road-walking nine more miles to town," I said. "And then by the time we got to the McDonald’s they were just about ready to close. There wasn't even enough time to get dry before we were forced back outside to walk up and down the road to find a place to sleep. On the outskirts of town, we saw a strip of trees cut out of a hillside for a row of power lines, so we climbed up there to setup camp."

“Yeah, I remember that," he said.

"That was kind of a shitty day," I said.

"It was kind of shitty wasn't it,” he said, but I could hear his smile.

“I'm mentioning it because when I thought about it today, I got very nostalgic. I miss it," I said. "Even the shitty days, I miss."

"So, as sort of an experiment, I thought about some really great days before backpacking. Memories of childhood, of trips, of friends. Memories of laughing so hard that the room goes silent because nobody can catch their breath. You know those laughs?” I said. “By every measurement, they were great days. But they didn't give me the same feeling. I guess I’d call the feeling homesickness, but I've never actually felt homesick before.”

“So you’re saying the worst day on the trail is better than the best day off the trail?” he said, summing it up much more succinctly.

“Exactly, but it's more than that," I said. "I even feel nostalgic for that night we slept on the front porch of that restaurant in Manchester Center to get out of the pouring rain. You were like, 'Hey, the sign says they don’t open for breakfast! I guarantee nobody will come in before 10!'”

"Yeah," he laughed, "And they didn't, did they?"

“No, but that was a shitty night too. I felt weird about unpacking my gear and getting into my sleeping bag, because I wanted to be able to make a run for it if I had to. God, I froze my ass off that night,” I said. “I think I got about two hours of sleep.”

"Nah, we were fine," he said. "If anybody saw us, they would have just told us to leave."

"Yeah, my attitude about that changed eventually," I said. "By the time we slept on that Big Lots loading dock in Morrisville, I wasn't too worried about getting caught. Actually, I slept like a baby that night."

And on the conversation went for hours. It became instantly clear that Red was suffering from the same sort of homesickness. The phone calls became more frequent and soon the conversations went from reminiscing about past hikes to planning the next.

As of today, that plan is to leave in March of 2014. Actually, for the first month, we deliberately have no plan other than to slowly hitch our way to Campo, California, a small town on the Mexican border. From there, we'll hike north along the Pacific Crest Trail through the Mojave Desert then over the crest of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountain Ranges. Five months and 2,663 miles later, we’ll cross over the Canadian border.

In the meantime, I'm working two jobs seven days a week to save money. The PCT is fully funded, but I have other big trips in mind after that, so I'll continue to work as much as possible to make those happen as well.

People have asked me how I'm able to afford to take so much time off of work to backpack. "Are you a self-made millionaire or something?" someone asked. That made me laugh. Even if every dime I've ever spent were returned to me, I still wouldn't be a millionaire. I don’t think it really occurs to most people how little money you actually need to live on the trails.

What could you afford to do if you had no mortgage, no student loans, and no credit card debt? Where could you afford to go if you had zero appetite for the latest gadgets, or newer cars, or expensive clothes? What if you had no rent, no electric bill, no furnace that needs replacing? No car payment, auto insurance, or vehicle maintenance or upkeep. What if you had no desire for a bigger TV or a more deluxe cable package? What if you had no need to contribute to a vacation fund and no reason to retire?

You might be able to spend most of your life doing what you love instead of just working toward retirement. What would I do with my retirement anyway? Do like the retired men I met on trails, who waited until retirement to go backpacking?

“It rained almost every day on that trip,” he said.

“True, that rain was relentless. I don't think we had two days in a row without rain on that trip," I said. "We hiked seventeen miles of muddy trail to the road then decided to hitch to the McDonald's in Brandon, so we could be warm and dry for a change.”

“Except, nobody picked us up,” he said.

“Yeah, so we ended up road-walking nine more miles to town," I said. "And then by the time we got to the McDonald’s they were just about ready to close. There wasn't even enough time to get dry before we were forced back outside to walk up and down the road to find a place to sleep. On the outskirts of town, we saw a strip of trees cut out of a hillside for a row of power lines, so we climbed up there to setup camp."

“Yeah, I remember that," he said.

"That was kind of a shitty day," I said.

"It was kind of shitty wasn't it,” he said, but I could hear his smile.

“I'm mentioning it because when I thought about it today, I got very nostalgic. I miss it," I said. "Even the shitty days, I miss."

"So, as sort of an experiment, I thought about some really great days before backpacking. Memories of childhood, of trips, of friends. Memories of laughing so hard that the room goes silent because nobody can catch their breath. You know those laughs?” I said. “By every measurement, they were great days. But they didn't give me the same feeling. I guess I’d call the feeling homesickness, but I've never actually felt homesick before.”

“So you’re saying the worst day on the trail is better than the best day off the trail?” he said, summing it up much more succinctly.

“Exactly, but it's more than that," I said. "I even feel nostalgic for that night we slept on the front porch of that restaurant in Manchester Center to get out of the pouring rain. You were like, 'Hey, the sign says they don’t open for breakfast! I guarantee nobody will come in before 10!'”

"Yeah," he laughed, "And they didn't, did they?"

“No, but that was a shitty night too. I felt weird about unpacking my gear and getting into my sleeping bag, because I wanted to be able to make a run for it if I had to. God, I froze my ass off that night,” I said. “I think I got about two hours of sleep.”

"Nah, we were fine," he said. "If anybody saw us, they would have just told us to leave."

"Yeah, my attitude about that changed eventually," I said. "By the time we slept on that Big Lots loading dock in Morrisville, I wasn't too worried about getting caught. Actually, I slept like a baby that night."

|

| (Photo: The Canadian/Vermont Border) |

As of today, that plan is to leave in March of 2014. Actually, for the first month, we deliberately have no plan other than to slowly hitch our way to Campo, California, a small town on the Mexican border. From there, we'll hike north along the Pacific Crest Trail through the Mojave Desert then over the crest of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountain Ranges. Five months and 2,663 miles later, we’ll cross over the Canadian border.

In the meantime, I'm working two jobs seven days a week to save money. The PCT is fully funded, but I have other big trips in mind after that, so I'll continue to work as much as possible to make those happen as well.

People have asked me how I'm able to afford to take so much time off of work to backpack. "Are you a self-made millionaire or something?" someone asked. That made me laugh. Even if every dime I've ever spent were returned to me, I still wouldn't be a millionaire. I don’t think it really occurs to most people how little money you actually need to live on the trails.

What could you afford to do if you had no mortgage, no student loans, and no credit card debt? Where could you afford to go if you had zero appetite for the latest gadgets, or newer cars, or expensive clothes? What if you had no rent, no electric bill, no furnace that needs replacing? No car payment, auto insurance, or vehicle maintenance or upkeep. What if you had no desire for a bigger TV or a more deluxe cable package? What if you had no need to contribute to a vacation fund and no reason to retire?

You might be able to spend most of your life doing what you love instead of just working toward retirement. What would I do with my retirement anyway? Do like the retired men I met on trails, who waited until retirement to go backpacking?

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photo: Splake and the Presidential Range

I took this photo in 2011 in New Hampshire's White Mountains.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

In the Presidential Range of New Hampshire's White Mountains, we stopped to savor this view. Actually, we didn't stop for the view as much as the view stopped us.

If it were exactly two months before, you would have found me at a desk staring at a computer screen. The cubicle walls surrounding me had been replaced by mountain views. Views that forced me to wonder why I wasted so much of my life slaving away. I guess it just seemed like the responsible thing to do at the time. I realize now how decidedly irresponsible that was.

My phone beeped in my pocket. At this elevation, it managed to find a strong enough signal to receive a text from a friend back in the real world.

"Ahh, why can't it be Saturday?" the message said.

I replied back, "It isn't Saturday? Funny, it definitely feels like Saturday."

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photo: Kayaking at Salamonie

I took this photo in 2009 at Salamonie Lake in North Central Indiana. You can order prints in my Etsy store. Use coupon code 5OFF2013 and receive $5 off any purchase of $15 or more.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

I set an alarm so I’d wake up a couple hours before sunrise. Between the silhouettes of trees, the lake’s black surface sparkled under a starry sky. I switched on a lantern and rolled out of my hammock.

At the edge of my campsite was an eroding hillside that sloped into the lake. Barefooted and with a lantern held out in front of me, I climbed down the crumbling dirt to the water’s edge. My kayak bobbed slowly on the waves, bumping into the fallen tree trunk where I had it secured with rope.

Years before it became the primary focus in my life, this was one way I satisfied my need for adventure, short camping trips fifteen miles from home.

I climbed into my kayak, scooted away from the shore, and paddled toward an island in the middle of the lake. When I was close enough, I fastened the paddle to the top of the boat and slid forward into the hull, so I could lie on my back for a better angle on the stars.

I couldn't help but doze in and out of sleep. For a time, the only sound was water lapping against the boat. Then the sun came.

This moment was the main reason I was on the water so early. A few weeks before, I drove out to the lake at three in the morning to paddle around in the dark. Moments before daybreak, I heard a lot of commotion coming from a small island, so I paddled closer. It seemed every bird in the county decided to rendezvous here that morning. Soon there was so much chirping from so many species of birds that it ceased to sound like chirping, like when a clap becomes an applause.

I’m not sure why they all flocked to this place, but it wasn't only birds. After the sun peaked over the horizon, two river otters surfaced only a few feet from my kayak. One swam straight toward me so fast I thought he might try to leap into my boat to either lick my face or rip it off. I had zero river otter experience, was this aggression, curiosity, or playfulness? I was so excited to take their photo that I momentarily forgot how to operate my camera. I snapped a couple shots of unidentifiable brown blurs then they were gone. I did manage to gain my composure enough to take this photo, which I like well enough, but I'd love to see a river otter in the shot.

After the sun was fully above the horizon, the birds quieted down, but I saw two deer on a peninsula jutting out into the lake, so I paddled closer. While one grazed the other suddenly ran toward the water and leaped in with a big splash. It swam like a Golden Retriever toward Monument Island, a nature preserve in the middle of the lake. I paddled as fast as I could to coast along beside her, but my presence scared her off course. I wasn't sure how long deer could swim and I wasn't prepared to save a kicking and drowning deer with my kayak, so I backed off then paddled to her other side to steer her back toward the island.

Then I saw another brown mammal swimming along the shore. I paddle toward it quickly hoping to have another chance to get my river otter picture. It was a beaver. I took a few unimpressive pictures. Soon the surge in wildlife withdrew and the lake would go back to its normal self. Full of motor boats and skiers, fisherman and loud radios blaring from pontoons. But I felt like I learned one of the lake's great secrets. And so, like the crowd of birds who packed themselves together on every available branch on that little island; I came back to this place at this same time every chance I got.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photo: Bee at Devil's Tower

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

I hiked all day around Devil's Tower National Monument, in Wyoming, to find a better angle to take its picture. I took dozens of photos, but didn't love any of them. I decided I needed to be by the river, which required climbing a fence and trespassing. Many prairie dog heads popped out of the ground to keep a close watch on me. After a few photos, I still wasn't in love with any. Then this bee started flying around me, so I increased the aperture, sped up the shutter speed and took its picture instead. The bee is still a bit blurry, but I like it anyway.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photography: The Rocks at Ryan Mountain

I took this photo in March 2012 in Joshua Tree National park. You can support my blog by ordering prints of this or other photos in my Etsy store. Use coupon code 5OFF2013 and receive $5 off any purchase of $15 or more.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

After we climbed about halfway up Ryan Mountain in Joshua Tree National Park, my friend Liv pointed down to this huge rock and said, "I'm going to climb on top of that when we get down."

While traveling across the country from national park to national park, it amazed me the places she would climb without the safety of ropes and harnesses. Sometimes I would hear strangers whispering things like, "look at that girl over there, she's crazy," or "you'll never see me doing that."

After leaving the Ryan Mountain summit, she beat me to the bottom, but I couldn't find her anywhere. I waited by the car for a little while then walked around to look for her. I started to wonder if she took a wrong turn. Then I heard a familiar whistle.

Liv and I met on the Appalachian Trail. When we couldn't find each other, we'd whistle back and forth until we honed in on each other's location. So, I whistled back. She whistled again. It was coming from the top of this giant rock. Suddenly, I remembered her saying she said she was going to climb on top of it. I looked up and there she was. She's a woman of her word.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photography: Tendril at Indiana Dunes

I took this photo in Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in 2010. You can support my blog by ordering a print in my Etsy store. Use coupon code 5OFF2013 and receive $5 off any purchase of $15 or more.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

While traveling in the Pacific Northwest, after I told people I was from Indiana, they acted as though their immense soaring views must be utterly mind-blowing to a flatlander hayseed like myself. It almost solicited a feeling of Midwesterner pride in me. Although they were right, of course.

I've long held romantic ideas of the west. As a kid, traveling west seemed like travelling to another world. They had mountains, geysers, and wildlife that didn't exist in my small patch of Earth. My world existed in a place where the views through the windshield were largely determined by the current height of the corn.

Sometimes I think my appreciation for nature and romantic view of the west wouldn't exist if not for my Midwestern roots. Might I have grown up thinking mountain views were ordinary? Would they have the same power over me? This picture, however, reminds me that my love of nature goes deeper than that. I look at this photo with the same sense of awe as any grand mountain view.

I spotted this tendril grabbing onto a branch for support while hiking through Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. I tend to forget that plants aren't stationary. In fact, they are rarely still. They simply live by a different clock than we do.

No matter where I live, a major part of me will always live somewhere out west, but beauty in nature is everywhere. You just have to stop and look.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photography: Deer at Mokowanis Lake

This is Mokowanis Lake in Glacier National Park. I took this photo in August 2012. You can support my blog by ordering prints in my Etsy store. Use coupon code 5OFF2013 and receive $5 off any purchase of $15 or more.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

To access Mokowanis Lake you must get off the main loop and stroll down a quiet spur trail, so it was a peaceful, less frequented, spot to set up camp.

The distant sound of a waterfall gave a constant background of white noise while I sat by that unbelievable turquoise lake for hours reading a book. Occasionally, I saw a deer grazing on foliage or sipping the lake water. It seemed as approachable and unafraid of people as a stray Labrador Retriever. It even wagged its white tail.

After the sun set, I retreated to my tent. I was still reading after dark under headlamp light when something moved outside my tent. I slowly poked my head out to see what it was. It was just the deer. I zipped the tent shut and went back to my book. Then I heard my trekking poles clack against a log. I stuck my head back out and saw the deer with one of the handle straps in his mouth sucking on the accumulated salty sweat.

“Hey! Stop that!” I yelled. Its eyes shifted over to me and it paused for a moment as if contemplating its next move. Suddenly, it grabbed the pole's handle in its teeth and took off into the woods.

“I paid $80 for those you son of a bitch!” I yelled while shoving my bare feet into my shoes. She didn't care though, what’s $80 to a deer? Chump change is what. I ran into the woods after it, leaping over logs and trampling through leaves. After a short chase, she stopped with the pole hanging from her mouth. She looked at me with that long dumb deer face.

“Drop the pole, you stupid deer!” I yelled and the pole dropped to its feet.

“What? I ain’t got anything,” its expression seemed to say. “Nah, nah, man. That was that other deer.”

For a moment, we stared each other down like it was high noon in Dodge City. Suddenly, she bolted into the woods leaving my saliva-drenched trekking pole on the ground.

I walked back to my tent with my pole in hand, victorious.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Photography: Bleeding Heart

This wasn't actually taken from a trail like my other photos, but I liked it so wanted to include it here. I took it in my old backyard before leaving for the Appalachian Trail. This may surprise you, but I used to have a house before I started all this.

You can support my blog by ordering a print of this photo in my Etsy store. Use coupon code 5OFF2013 and receive $5 off any purchase of $15 or more.

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO...

There isn't much of a story actually. The woman who lived in the house before me had the two-acre property looking like a city park. There were several species of trees, a creek, and a wide variety of wild flowers. The first year I lived in the house, I never knew what flowers might pop up next. This one was my favorite.

The lack of a story for this photo is the biggest endorsement I can give for getting out and seeing the world. Living for the anecdote is a great way to ensure you'll live an adventurous and fulfilling life.

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

The Before Interview with Victor Maisano, 2013 Appalachian Trail Thru-Hiker

Earlier today, Victor Maisano officially began his thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail (you can follow him and his crew at BackpackingAT.com).

If you're reading this you probably know I've been answering some of his questions about the trail. Before he left I turned the tables and asked him a few. I thought it would be interesting to ask them before and after to see if, and how, his answers have changed.

The first few questions, however, I asked because I like knowing what motivates others to take on such a challenge. . Are they an adventurer discontented by a cubical life? Do they just want to challenge themselves? Did they conceive the endeavor when things in life seemed to be falling apart or when everything finally came together?

Hundreds of people head to the Appalachian Trail with a unique story and personal motivation. I love seeing how all their stories converge.

RG: When did you

first hear about the Appalachian Trail?

VM: I believe

I first learned about the Appalachian Trail in Boy Scouts. There is a fifty-miler badge I always wanted to get, but never had the chance to earn.

RG: When did you

start dreaming of doing it? Or what finally inspired you to take this on?

VM: Oddly

enough when I was in Costa Rica. Even though I was living the Caribbean dream and saving turtles 24/7, the water always seemed to be clearer in the other pond.

Throughout my thought process of "what is next" after volunteering at

a Sea Turtle Conservatory, I knew I was not ready to head back to a

"normal" life back in the corporate world full time. So looking to

challenge myself physically and mentally the Appalachian Trail came easily to

mind. My mind was fully set after skimming a couple of articles online and

bouncing around previous AT thru-hikers blogs. I would imagine myself in their

shoes/pictures!

RG: What are you most looking forward to?

VM: Meeting great people, seeing random animals (other than the ones you find in suburbia) and attempting my wilderness survival skills from time to time.

VM: Meeting great people, seeing random animals (other than the ones you find in suburbia) and attempting my wilderness survival skills from time to time.

RG: What do you hope to get out of this experience?

RG: What are you most looking forward to?

VM: Meeting great people, seeing random animals (other than the ones you find in suburbia) and attempting my wilderness survival skills from time to time.

VM: Meeting great people, seeing random animals (other than the ones you find in suburbia) and attempting my wilderness survival skills from time to time.RG: What do you hope to get out of this experience?

VM: New perspective from this hiking community and learn all that I can from the experience that I would not have from reading about it.

RG: What was your first big adventure?

RG: What was your first big adventure?

VM: I would like to think my first big adventure was when I headed to Vietnam for 2 months with my older (adopted Vietnamese) Brother when I was 15ish. Sleeping on dirt floors, eating interesting meals (including dog) and being the only white person in these small villages was certainly an eye opener for what the vast opportunities the world has.

RG: There are a lot of unknowns that you wonder about when planning a hike like this. What are you

biggest concerns?

VM: To be

honest it's power. I plan to be very social media savvy and fear the amount I

want to update will not correspond with amount of juice I am bringing - granted

I am bringing solar panels through the green tunnel. Other than that it's my

lack of Knives. At the moment I am bringing a smaller sized serrated knife.

Seeing as He-Man and Leonardo were able to protect themselves from all sorts of

enemies, I figured that's what I need. However I know that Skeletor nor the

Shredder will be anywhere near the trail.

RG: What is your current pack weight?

VM: Yikes sensitive topic. I think right now it's 45ish lbs.

RG: I agree it can be a sensitive question. It's often followed by someone with an ultralight pack telling you you're doing something wrong. I only ask because I want to see if, and how much, it changes by the time we do this interview again. So, what is your favorite gear item right now?

RG: I agree it can be a sensitive question. It's often followed by someone with an ultralight pack telling you you're doing something wrong. I only ask because I want to see if, and how much, it changes by the time we do this interview again. So, what is your favorite gear item right now?

VM: To be honest it's my Osprey 65L Backpack. Never before in my life had I had a backpack that of a quality nature. This pack feels like I am giving my little nephew a horsey back ride and he's holding on tight!

RG: How are you preparing (physically, or mentally)?

VM: Physically

I am not - I am solely relying on my youth to start me off. I know this not the

smartest idea, but I feel my body is very adaptable. Plus I won't complain even

if was having a hard time.

Mentally - I have been trying to imagine myself on the

trail and going through the various scenarios. Reading other peoples blogs and

just speaking with previous section and through hikers has been great as well!

RG: Yeah, physically the best way to prepare is to backpack before heading out, which can seem a bit redundant if you're not trying to break a speed record. Have you backpacked before? What's the longest you've

ever hiked?

VM: I have

backpacked 2 sections of AT Before. Both in/near the Smoky Mountains, with a

small group of friends for 50 miles over 4 days.

RG: Do you have more adventures in mind after this one?

VM: Next adventure is TBD. I would not mind switching back and forth between water and land based adventures. My mind has been definitely wandering, but my bank account says I need a job BADLY. Perhaps I can combine the two?

VM: Next adventure is TBD. I would not mind switching back and forth between water and land based adventures. My mind has been definitely wandering, but my bank account says I need a job BADLY. Perhaps I can combine the two?

RG: Combining the two is a dream of all wanderers, but the good news is many find a way. And the Appalachian Trail can make anyone realize how little income and possessions they really need, which will get you halfway there.

Last question, do you have a trail name yet or do you prefer the

tradition of letting it happen on the trail? Some people prefer to go into it with

a name already chosen to avoid a bad name. For example, for most of my hike I was called Nancy Drew, but not everyone will be so lucky.

VM: I do not

have a trail name. I would prefer the traditional route. However I have a

feeling with my personality and friends, this will be very random and most

likely not reflect me. But I'll go with it.

RG: I'm sure we'll find out very soon what it will be on your blog at BackpackingAT.com. Thanks for your time Victor and good luck out there!

RG: I'm sure we'll find out very soon what it will be on your blog at BackpackingAT.com. Thanks for your time Victor and good luck out there!

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Q&A: Bugs and Other Pests on the Appalachian Trail

Victor asks for tips in dealing with pests and other natives of the Appalachian Trail, such as Ticks, Flies, Mice, Poison Oak, Poison Ivy, and any others not on his radar. I’m going to break his question up in parts.

First, let me just remind you that Victor's hike begins this Thursday (March 28th), join me in following his progress at BackpackingAT.com.

VM: From what I hear, knowledge is power. Is it true that learning how to prevent visitors is half the battle, or is it inevitable?

RG: Yes and yes. There are ways to reduce potential issues with the bugs and wildlife, but it comes with the territory. There are different guidelines for different pests that I’ll go into below.

Ticks

Ticks

VM: Do you have any useful hints for removing ticks? Is it true a drop of turpentine will make the ticks dig themselves out?

RG: Good question. Ticks are the worst. I'd honestly rather see a black bear on the trail (actually I love seeing black bears, so that's a bad example). I only saw two ticks crawling on me while hiking the AT, but I also met two hikers who contracted Lyme Disease, so it's good to know a few things about them before heading out.

There are several myths about tick prevention and removal. Using heat or covering the tick with anything in order to coax it back out can only make the problem worse. It can actually cause them to regurgitate more saliva (and potentially more pathogens) into your bloodstream.

The hypostome, i.e. mouth parts, that they burrow into your skin, looks similar to a tiny barbed harpoon. Also, some ticks, like the Lyme-Disease-spreading deer tick, secrete a cement-like substance to keep themselves securely attached to your skin while feeding. In other words, they can't back out quickly even if they wanted to. The longer the tick is attached, the higher your risk of infection, so the goal is to remove the tick as soon as possible.

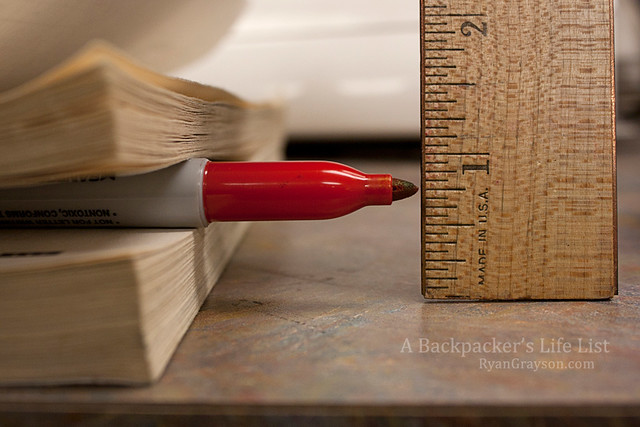

The best way to remove a tick

The best way is with tweezers. Some ticks, like the Deer Tick, can be as tiny as a poppy seed, so you’ll need tweezers that can grab something that small. Grab the tick as close to your skin as possible and slowly pull it straight out. Clean the skin around the bite with alcohol. If the hypostome (mouthparts) remain stuck in your skin, don’t worry about it. Doctors aren't concerned about it, so I'm not either. Also, when the hypostome breaks it may even send germs and saliva further back into the ticks body and saliva glands.

Lyme Disease

The biggest concern with ticks on the Appalachian Trail is Lyme Disease. There are 30,000 to 40,000 cases in the United States annually and about three out of four are reported in ten of the states along the Appalachian Trail.

Here they are in order of highest cases per capita: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York, and Virginia.

Here they are in order of highest cases per capita: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York, and Virginia.

If you experience any symptoms like a rash or fever, consult your doctor and let them know you've been bitten.

Preventing Ticks

Chances are you'll hike the entire Appalachian Trail without having a tick burrow into you, but with a few precautions, you can reduce your risk of getting Lyme Disease to nearly zero.

Do a daily tick check

Full disclosure, the longer I went without seeing a tick the less frequently I would do a tick check. Eventually, I only checked after hiking through bushy areas with tall grass or loose dry leaves on the ground. My laziness aside, daily checks are by far the best way to prevent the spread of Lyme Disease. It generally takes at least 24-48 hours for a tick to transmit the disease, so if you're doing daily checks, it's unlikely you'll get it.

Thorough tick checks are important since their saliva has anesthetic properties. That means you won't feel them burrowing or feeding. Additionally, they are hard to find because some, like the deer tick, are as small as a fleck of dirt, which you'll be covered in most of the time. They also have a tendency to search for places on your body that are hard to see without a mirror... and places your friends will not volunteer to check for you.

Bug Repellent

I'll go into this deeper below, but DEET is still the most effective bug repellent. Nothing really comes close in effectiveness, duration of effectiveness, and cost per ounce. There are a lot of home remedy bug repellent myths out there, but none have been shown to be effective for more than a few minutes, if effective at all. Don't waste your time or risk going without an effective treatment. A 23 to 33% DEET solution is the way to go and it's safe if used properly.

Wear Light Colored Clothing

Even though I didn't have any biting ticks on the Appalachian Trail, I did find a couple crawling on my pant legs. It happened after scouring the woods for firewood in Shenandoah National Park. Since I wore light brown khaki pants they were easy to spot.

Walk in the center of trails

Those minuscule SOBs are hanging onto plants with their little legs outstretched waiting for a blood-filled mammal to walk by. Avoid their reach by walking down the center of the trail whenever possible.

Some months are worse than others

Peak tick season starts in late-April to early-May and lasts all through summer. That doesn't mean you won’t get ticks on you in October, though. Actually, that's when I found them on me in Shenandoah. In other words, they are going to be around during your entire hike, but they will probably be worse Late-May through Early-August.

Signs of Lyme Disease

Check out the Centers for Disease Control's web site for more information, but I'll give you a summary. One of the first signs that you have contracted Lyme Disease, which will normally occur 1 to 2 weeks after infection, is the development of a bullseye-shaped rash around the bite, although sometimes there won't be a rash at all. Lack of energy is another common first symptom, but you'll feel that on your hike either way. Other symptoms include fever, chills, headache, stiff neck, swollen lymph nodes, muscle pain, and joint pain.

If you do have symptoms, see a doctor as soon as possible. The longer you go without treatment, the worse symptoms will get and it can get incredibly nasty. If you find a bullseye-shaped rash or feel symptoms of the flu, get checked. If you do pull a tick off your body save it in a Ziploc bag so it can be tested later if symptoms do appear.

Mosquitoes and Black Flies

Even though, you could hike the entire Appalachian Trail without seeing a tick, mosquitoes may become the bane of your existence. I doubt you'll have much trouble with black flies, since they are worst in Maine from Mid-April through Mid-June.

Prevention

There will be days where this seems like an impossible task. There is no way to keep all mosquitoes at bay, but you can prevent them from driving you crazy.

Bug repellent

As I said previously, the most effective bug sprays on the market contain 23% to 33% DEET. Several studies, and my own personal experience, have shown that a higher concentration is basically just as effective. I also use Permethrin on clothes, but more on that in a bit.

I used to carry a 1 oz. eyedropper of 100% DEET oil, but sprays seem to be more effective. The eyedropper is ultralight, but this is where I'll sacrifice a couple ounces. Your happiness and sanity do have value after all. Many people use the eyedropper method by putting a few drops on the back of their neck, lower legs, wrists, and other strategic places, but it is believed that DEET works by surrounding you in a vapor that disrupts the bug's ability to sense humans and other animals. In my opinion, a few drops here and there just don't seem to create enough of this vapor barrier. Some people attract mosquitoes more than others, though, so my experience may not be the same as someone else's. I draw them in like I'm their mecca.

When using DEET, avoid getting it in your eyes, ears, nose, or on water bottles and food. Also, DEET can dissolve certain plastics, rayon, spandex, and other synthetic fabrics such as the lining in some raincoats. Be careful not to get it on the palms of your hands, so you don't ruin any gear. Since ticks and mosquitoes aren't much of a concern during a rainstorm, wipe any DEET off your skin that may come in contact with the lining of your rain gear before putting it on. A gear expert said DEET was the reason my Marmot raincoat lining was peeling off.

Is DEET safe?

DEET sounds horrible, right? After all, it can breakdown certain plastics and synthetic materials. You’re probably thinking, why would I want to put something like that on my skin?! Well, Vodka, vinegar, and Coca-Cola can dissolve a number of things too, but they won’t harm your skin.

It’s not hard to find someone who believes anything unnatural is going to kill you slowly, but if used properly DEET is safe. Of course, nothing is 100% safe, but don’t forget we are using them to avoid things like Lyme Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and West Nile Virus, which are far worse.

That said, using it properly is not always convenient on a long distance trail. For example, using it properly means you need to wash it off your skin at the end of the day. Since showers are rare on the AT, and since you don’t want to get DEET in the aquatic ecosystem, you’ll need to go at least 200 feet from a water source to rinse it off. Since mosquitoes are only a problem in warm weather, you won't have to worry about rinsing off when it's dangerously cold. Also, rinsing off is a good practice anyway since cleaning up at the end of the day will make you feel, smell, and sleep better.